Movement/Architecture: Dwelling in Hornsey Town Hall as an Impetus to Process

Note: I originally wrote this text for a 2019 practice-as-research presentation when I was programme leader for MA/MFA Creative Practice at Trinity Laban Conservatoire of Music and Dance. At the time, I thought I might try to publish it an academic journal, but with my decision to step away from academia, that plan never came to fruition. As I work on a staged telling of the Movement/Architecture story — a sort of performative or choreographic essay, if you will — I have revisited this piece as source material and decided to share it here. Movement/Architecture is a living process and some of my views on this will have shifted, but in general what is written here holds true and is a solid account of how the work began.

Abstract

This article is a practice-led account of the genesis of Beautiful Confusion Collective’s Movement/Architecture project, a site-responsive choreographic practice for mapping, storing and evoking the architectural features and ambience of spaces in flux, with a particular focus on an Arts Council England-funded R&D in autumn of 2016. It considers an extended period of dwelling within North London’s Art Deco Hornsey Town Hall, during its period (2015-2018) as a temporary arts centre, as creating the necessary conditions to develop a multi-sensorial (following Juhani Pallasmaa), ‘soft focus’ (following Ann Bogart and Tina Landau) engagement with the building’s interiors, an awareness which led to the creation of a process that dances with, rather than within, architectural spaces. While the Movement/Architecture practice has grown beyond Hornsey Town Hall (HTH), the article considers the sociocultural - and architectural - implications of a project like Hornsey Town Hall Arts Centre (HTHAC) as constituting an interregnum in the status quo governing both the economics of cultural production in London and architecture’s power to regulate space and influence behaviour. As the HTHAC project ends, the character of the Movement/Architecture work is considered in relation to discourses around elegy and the materialisation of memory. (202)

Keywords: architecture, repurposed space, embodied memory, gentrification, improvisation, dwelling

Movement/Architecture is a dance that began from an act of dwelling, specifically the opportunity I was afforded to dwell within Hornsey Town Hall for an extended period. The opportunity arose late in 2014, when ANA Arts Projects obtained permission from Haringey Council to open the building as an arts centre that would be run on an interim basis while the future of the building was determined. I had lived in Crouch End for three years at that point and had never been inside. I was vaguely aware of the brick facade of the building towering over the often non-functional fountain behind the green at the back of the W7 bus stop, but knew little about its history, or current prospects. It looked, in a way that persisted even after it was occupied, incredibly, impenetrably, shut.

And then, suddenly, it was opening. A chat with ANA’s Executive Director Nick Saich at an open evening led to a meeting with Artistic Director Alex Rochford. I pitched the idea of operating a studio for physical theatre and dance companies on a model similar to that of hot-desking, which would allow artists regular access to development space. We combed through the available spaces and settled on what must have been a former office overlooking an overgrown central courtyard. When I first saw it, it was crammed with wooden chairs, office furniture and what seemed like an infinite number of dead moths. By the time it was cleared and began to operate as Studio 4, a black dance floor had replaced the chaos. The walls had once been painted a distinctly municipal shade of green that was oddly calming. It was a private and light space in which to work, to dwell. Later, as I came to know more about the building, I would discover that the assessors of the planning competition to design it had praised architect Reginald Uren’s design for its ability to “turn inwards and secure light from the site” (“Assessors’ Notes”, Haringey Archive, 1935.)

At the time, and even more so now, writing in the first month after the conclusion of the ANA’s interim project, I was/am struck by the improbability of such dwelling, which is unusual anywhere, but particularly so in London’s economic situation, which so often makes us squeeze as much as humanly possible into increasingly smaller increments of time and space. While first-time visitors would marvel at the architectural detail of the Art Deco building, for me its most salient aspect was its availability. Because generally places are available only for a short time and with clear limits - don’t go into this part of the building, make sure you’re out by 6pm, etc. etc. Unless you want to stay longer, in which case it’s £30 an hour. Plus VAT.

Hornsey Town Hall was, remarkably, not like that. The type of dwelling it offered to its resident artists calls to mind Gaston Bachelard’s characterisation of the house: “In the life of a man, the house thrusts aside contingencies, its councils of continuity are unceasing. Without it, man would be a dispersed being” (2014: 28-29).

On one hand, it’s impossible to read Bachelard in 2019, in London, in a climate of extreme precarity around housing, let alone rehearsal space. The notion of continuity has the aura of sweet, unattainable luxury! But if we replace continuous with sustained, we can start to get at what was on offer at HTHAC, the specificity of what it is to dwell in a building, especially a former municipal building, erected in 1935 and gradually abandoned beginning in the 1960s, when the former Borough of Hornsey was subsumed into the London Borough of Haringey and the council headquarters moved to Wood Green.

Anne Bogart and Tina Landau’s description of ‘soft focus’ in The Viewpoints Book offers a practical, embodied way in here. Bogart and Landau’s ‘soft focus’ is one of the five images that travel continuously with Viewpoints training, a method of performer training and composition they evolved from Mary Overlie’s Six Viewpoints. They write: “Soft focus is a physical state in which we allow the eyes to soften and relax, so that, rather than looking at one or two things in sharp focus, they can now take in many” (2014: 31). This gaze differs radically, they argue, from the way we generally look in everyday life. Direct gaze wants something; it’s intentional, high stress, single-focused, closing off the other senses, “[l]ike a hunter after prey . . . narrowed down to a preconceived series of possibilities” (Ibid). Soft focus, in contrast, “develops a global perception,” (Bogart and Landau, 2014: 31-32). It invites wonder, opens time and space, reminds us we have bodies and senses other than vision; it invites us to take our time, to meander, to be indirect.

Before Movement/Architecture crystallised for me as a specific creative practice in, of and with the building, it began to happen anyway, through dwelling, in the way casual conversations can deepen into friendship, or even love. I had developed a festival (The Impermanent Festival of Contemporary Performance, aka ImpFest) with Jamie Harper, a theatre director whose company Hobo Theatre was resident in the building via the hot-desking, studio-share scheme. With many spaces in the building in use as performance spaces during the festival, I was given a small panelled room on the newly designated performing arts corridor as a dressing room and warm up space to use before my solo performance, which occurred eight times over the course of September 2015. At some point during the festival, I started dancing with this space, as a kind of warm up. I say dancing with intentionally, as distinct from dancing in. HTH has a number of these remarkable, fully panelled rooms, with built-in cabinets that invite you to open them and to make contact with the patina, to touch, smell, give weight to something that has been there since 1935. This panelled room was much smaller than the studio I usually worked in, but I began to go there, even after the festival had ended, to continue this relationship, this dancing with.

That a duet with architecture should arise out of a soft focus period of dwelling in the interiors of HTH is hardly surprising, especially when placed in dialogue with the field of architecture and the role of the senses in our apprehension and experience of buildings. In The Eyes of the Skin, Juhani Pallasmaa laments the dominance of the visual sense, writing:

The hegemonic eye seeks domination over all fields of cultural production and it seems to weaken our capacity for empathy, compassion and participation with the world. The narcissistic eye views architecture solely as a means of self-expression and as an intellectual-artistic game detached from essential mental and societal connections, whereas the nihilistic eye deliberately advances sensory and mental detachment and alienation. Instead of reinforcing one’s body-centred and integrated experience of the word, nihilistic architecture disengages and isolates the body […] The world becomes a hedonistic but meaningless visual journey. 2013: 25)

In this passage, the nihilistic eye is of particular relevance due to its disembodying impact. By contrast, the act of dwelling in an architectural space, in soft focus, has the opposite effect, as Bogart and Landau acknowledge: “By taking the pressure off the eyes to be the primary information gatherer, the whole body starts to listen and gather information in new and more sensitised ways” (2014: 31).

Had I not been dwelling in HTH, really dwelling, not in the sense of a time-limited residency, where the space is like spice added to a dish one is already cooking, but in a long, marinating sense, I suspect Movement/Architecture would not have come into being. Pallasmaa writes that “Experiencing a place, space, or house is a dialogue, an exchange: I place myself in the space and the space settles in me” (2011: 125). By the time Movement/Architecture became an idea it was possible to share with others, we’d reached that state, the building and I. We’d had time to hang out, to get to know each other, to settle.

As an explicit practice, rather than a by-product of dwelling, Movement/Architecture began with a pilot project in March 2016, a short film capturing improvised movement shot in the largely untouched women’s dressing room at the back of the main hall. By then, we were occupying the building with a ticking clock in the background – after all, this was always an interim project, though its exact end was always (often infuriatingly) uncertain. Despite my tremendous appreciation for the building’s availability, for the time and space it had given me, I found myself oddly ambivalent regarding efforts to save it from development, a view I voiced in a recorded conversation with my collaborator, dramaturg Mary Ann Hushlak, during our Arts Council-funded Movement/Architecture research and development period in October 2016: “I have a weird relationship to the campaign because even if…[it wins], I actually don’t think I’ll maintain access anyway…so it’s sort of…I don’t know where to put my energy in that fight” (Hushlak 2016). Listening back to the recording with the benefit of hindsight, I hear my ambivalence as a struggle to articulate the precise genus loci of HTHAC, the specificity of what was in the air, which didn’t feel compatible with any bureaucratisation, whether that emanated from developers, or a panel of concerned citizens.

Throughout its operation as Hornsey Town Hall Arts Centre, and particularly at the beginning, the building possessed a resolutely anarchic, ad hoc nature, which feels, to me, having lived it, intrinsically bound up in the juxtaposition and co-existence of the interim/DIY aesthetic of HTHAC and the permanent, municipal seriousness of HTH. The layering of these elements – the informal with the formal, the ad hoc with the designed, the mess with the beauty – gave the building a particular frisson and rendered it a particular kind of ‘available’ to the individuals and groups who came to use it. I find resonance between this type of ‘available’ and David Bergman’s discussion of the word’s etymology and associations: “the available is often the rejected, the unwanted, the cast away. To be available is to largely, although not completely, alone, unmoored, untied. […] The available waits in the dark to be used and when in use, recognises that it will be returned to the dark” (2018: n.pag.).

To a certain extent it is paradoxical to talk about HTH as surplus to requirements, given that the running of the arts centre occurred in an interregnum created by protracted wrangling over its future. Yet, simultaneously, it feels apt – the building had been steadily abandoned and fallen into disuse, parts of it into semi-dereliction. It had gone dark and was available for acts of illumination. To this extent, heightened by its status as the municipal centre of the extinct borough of Hornsey, it shares characteristics with the modern ruin, conceived by Celeste OIlalquiaga, following Walter Benjamin, as “cultural paradox and material surplus” “littering the cityscape with their eroding dreams, shapes and textures” (2017: n.pag.). I posit that the intersection of HTHAC’s particular type of availability, layered over with its ambiguous status as surplus, or remnant, together with an extended, period of embodied, soft focus dwelling, gave rise to Movement/Architecture as an imperfect, embodied methodology, for mapping and storing this rip in the fabric of London’s business as usual, and, eventually, other built spaces as well.

In Make it Real: Architecture as Enactment, architect Sam Jacob describes humans as residing under the jurisdiction of architecture - and this isn’t a neutral force: “Intentionally or not, architecture is the physical manifestation of societal will, an enactment of the intentions of government policy, capital, social convention and so on. […] In the most direct sense, architecture permits and prevents the ways in which we use space” (2012: 34). In other words, our behaviour in space is codified by the way in which that space has been built.

Pallasmaa takes a slightly different tack, asserting that “Architecture has always fictionalised reality and culture through turning human settings into images and metaphors of idealised order and life, into fictionalised architectural narratives […] It has a central word in creating and projecting an idealised self-image of the given culture” (2011: 19).

Taken together, these views position architecture as a reifying fiction, whose projection in space has very real consequences for where and how we live our lives. As a centre of municipal power, Hornsey Town Hall, particularly its more formal spaces, has power structures encoded into its make-up. Archival research into the competition to design the building, organised by RIBA, and the selection committee’s review of the submitted designs note the extent to which each succeeds in accommodating the diverse needs of the social, political and administration sections of the building into a single structure. A contemporary news article announcing the RIBA-adjudicated competition notes the “The Council are desirous that the character of the buildings shall be dignified, and they rely on good proportions and fitting architectural setting rather than on elaborate decoration and detail, which is not desired” (“Hornsey Gets a New Town Hall”, Haringey Archive). Uren’s winning design is praised as possessing “dignity and a definite civic character” (Assessors’ Notes, Haringey Archive). To engage with the building’s architecture is to encounter the values, contexts and ambitions of the post-WWI context that produced it. In its operation as HTHAC, however, there was also more.

Pallasmaa writes that “Architectural imagery has a […] central role in cinema, theatre, photography and figurative painting. These images create the sense of context and place, as well as the cultural and historical era for the depicted scene or event” (2011: 120). This assertion is borne out by HTH’s busy schedule as a film set, for a number of period projects, which leaned into the building’s aesthetic. Similarly, a 2015 production of The Trial, staged in the building’s courtroom-esque Council Chamber by the Crouch End Players, makes delightful, theatrical use of the space’s properties, which support the dramaturgy of the performance. This is space as set and it’s a good match.

What happens, though, when, instead, cultural production juxtaposes with the building? A contrast to The Trial is provided by Tania Batzoglou and Vanio Papadelli’s Candid, performed during ImpFest 2015, which, by comparison, challenges the built dramaturgy of the space, takes it as a playground, subverts it and, in so doing, challenges the hegemony of power articulated through recognisable structures. A defiant statement is made about power when the spaces designed for its exercise are occupied by performers who engage with the potentiality of the space - as playground - to an equal or greater extent than they engage with the initial purpose of the room. This is architecture as possibility, or, as Pallasmaa frames it, as provocation:

“Architectural images are promises and invitations: the floor is an invitation to stand up, establish stability and act, the door invites us to enter and pass through, the window to look out and see, the staircase to ascend and descend” (Pallasmaa 2011, 123-4). As a process, Movement/Architecture takes payment on these promises and accepts these invitations. The work is a dance with architectural space and simultaneously a choreographic technology for storing and mapping spaces in flux. But just as Jacob and Pallasmaa note the inherently sociopolitical dimension of architecture, so too the mapping and evocation of space that Movement/Architecture seeks to achieve is not simply a matter of mass, structures, angles and the play of light. What’s clear is also being danced, at this stage of the process, is the moment of in-betweenness that HTHAC inadvertently opened up. It’s about the architectural features, yes, but also about the brief, specific moment in which it was possible to dance with them.

Around the time of our Arts Council-funded R&D in HTHAC, in October and November 2016, Movement/Architecture emerged as a means of physically mapping and storing architectural spaces in the body, such that the performer’s subsequent performance has the capacity to evoke that space and its ambience for spectators who had never seen it. The idea to attempt this at all came out of the dwelling relationship I had with HTHAC and, also, came into increasingly acute conflict with the sense of time running out on the interim project.

In the background, as indicated above, was a sense that any outcome, other than perpetuation of the interim status quo, which seemed highly unlikely, if not impossible, was likely to lead to reduced access, increased bureaucracy and a tamping down of the anarchic ruling spirit of the place. This same sense is also reflected in an appeal to Haringey Council’s Cabinet from the Hornsey Town Hall Appreciation Society, delivered by community activist Clifford Tibber on 24 October 2016: “The old man of Hornsey must live, but not in a straightjacket of foreign investment, alone in a hotel cut off from merriment and mirth” (Robbins 2016). In other words, borrowing language from Bergman, the building would be “returned to the dark”, in terms of its availability to the individuals and initiatives then in place (2018: n.pag.). This is unsurprising, since HTHAC was an anomaly. It diverged, more or less radically, at different times in its existence, from the socioeconomic norms of cultural production in London. The extent to which it constituted an excess - of space, of availability - resonates with OIlalquiaga’s reference to George Bataille’s recognition of “this cultural ambivalence towards excess, which he proposed as la part maudie, the damned part, or ‘accursed share’: a surplus of cultural energy that must be disposed of so that it does not turn destructively on the society that produced it” (2017: n.pag.). In other, more quotidian terms, we were the equivalent of a pirate ship sailing in capitalist waters. Of course we weren’t going to be allowed to continue.

It’s impossible to make live performance and live in fear of ephemerality, so if I was going to find a way of memorialising the building, it was, of necessity, going to have to be temporary and imperfect. As I write, I feel my resistance to the word ‘memorialising’. It feels too dead, too staid, when what I really wanted to do was to capture the possibility of the building and its architecture, the glorious freedom it offered me, for two years, to interact with it - all of it, really - in pretty much any way and at any time that I chose to do so. I wanted to remember the energy that created, in the building, in my collaborators, in myself.

In the introduction to Spectral Spaces and Hauntings: The Affects of Absence, Christina Lee identifies “a shared anxiety over amnesia that has led to what Andreas Huyssen describes as a ’culture of memory’ that has become pervasive since the late 1970s; it manifests as an urgency to secure and monumentalise local and national histories amid globalisation and dramatically shifting political landscapes” (2017: n.pag.). Movement/Architecture has no desire to fix, or to monumentalise, nor is it well placed to do so, given that its instrument is the moving human body. While the technology exists to create a detailed architectural survey of the building (now ongoing as part of its redevelopment), or to document it exhaustively via still and moving images, Movement/Architecture operates in tune with OIlalquiaga’s assertion, that, in an age of advanced digital technology, “material things have become vestiges of a time when touch, or direct contact, still prevailed as a form of human perception and connection” and that virtual reality’s “intangibility generates a longing for what cannot be touched, as if concrete matter held a certain degree of reality that otherwise escapes us” (2017: n.pag.). The mission of Movement/Architecture, then, is to arrive at a point where it becomes possible to dance the concrete encounter with a building in absence, in the hope that, as Lee writes “the ‘appearance’ of absence, emptiness and the imperceptible can indicate an overwhelming presence of something that once was and still is, (t)here” (2017: n.pag.).

So if that’s where we’re going, how do we get there?

The process our team, which includes as core members myself, Hushlak and movement director and practical choreologist Sylvie Robaldo, has developed begins with preparing the performer to encounter space through a warm up that heightens sensitivity to space. This happens via an adaptable framework of provocations drawn from Bogart and Landau’s Viewpoints of Architecture and Robaldo’s knowledge of choreology and the Rosemary Brandt Practice (RBP). Viewpoints attunes our multi-sensorial perception to specific elements of architecture: the floor, large, fixed masses, the play of light and colour in a space, its smaller details. Choreological practice and RBP draw our attention to the movement qualities and dynamics with which we engage with these elements and the spectrum of positions (ranging from direct contact to projection in space) that it is possible to occupy in relation to space. There is a subjective element to this practice as well, as the performer may be invited, at this stage, to recollect a building she knows well and to imagine herself moving with and in it, allowing it to gently and flexibly overlay the landscape of the physically present space.

Following this period of work, which happens in a studio or other space which is not itself the subject of the Movement/Architecture work, we move into contact with actual spaces. During our period of R&D in HTHAC, we chose three spaces, with each one becoming the remit of a single performer.

Sílvia Almeida worked with the top flight of the building’s formal front staircase and the second floor landing onto which it leads. The materials used here are rich - marble, carved wood, glass, original lighting fixtures and clocks. The centre of the landing is carved out, into two sections, one rectangular and one square, which are surrounded by railings with wrought iron detailing that are too low to comply with contemporary health and safety requirements, as result of which the general public may not access this part of the building. The theme of danger continues with a locked, but wobbly door that appears to lead onto the roof, an inexplicable pile of sand that was present during the R&D and an explosion of cables and insulation protruding from the intersection of two walls.

If it is true, as Robert McCarter, quoting Louis I. Kahn writes, that “Rooms must suggest their use without name” (2016: 19), Alicia Cubells’ space, the previously discussed Council Chamber, was the most clearly determined and defined space of the three. Set out as an amphitheatre, built-in rows of desks and upholstered chairs form an arc facing a linear, raised platform at the front of the room. The floor, uniquely among the three spaces, is carpeted. The desks and chairs are a marvel - once, in the early days of HTHAC, I found a razor blade in a desk drawer. The chairs are upholstered in leather that has cracked, allowing stuffing to seep out, but all of this is covered, for conservation purposes, with vinyl slipcovers, giving the sense of something wild swept under the rug. The room is two stories to accommodate a viewing gallery and high, rectangular windows with bespoke iron fittings extend from chair rail height, embraced by dusty drapes and overlooking internal spaces. There is a sense of quiet completeness in this room; it feels like its own universe.

In contrast to Almeida’s and Cubells’ formal, presentational spaces, I chose to work in the building’s functional back staircase, which is accessed from the ground floor performing arts corridor and winds down to the basement and up to the second floor around a now-defunct elevator shaft. The staircase’s most remarkable feature are its curved windows - which open - that stretch the full length of the building. A bespoke, Art Deco handrail runs continuously, connecting wall to window to wall with barely perceptible, but perfectly engineered turns. As in the other spaces, there is a juxtaposition of elements: circular period light fixtures with an LED safety light; the chaos of the building’s forecourt viewed through the Art Deco beauty of the windows, with their bespoke metal fittings; the clean lines of the space broken up by generations of posters outlining fire evacuation procedures.

In working in these spaces, Pallasmaa’s statement that “an architectural work is great precisely because of the opposition and contradictory intentions and illusions it succeeds in fusing together” (2012: 32) became a frequent reference. It spoke to the building as a whole, as well as to each space individual and the richness and complexity of our encounters with them.

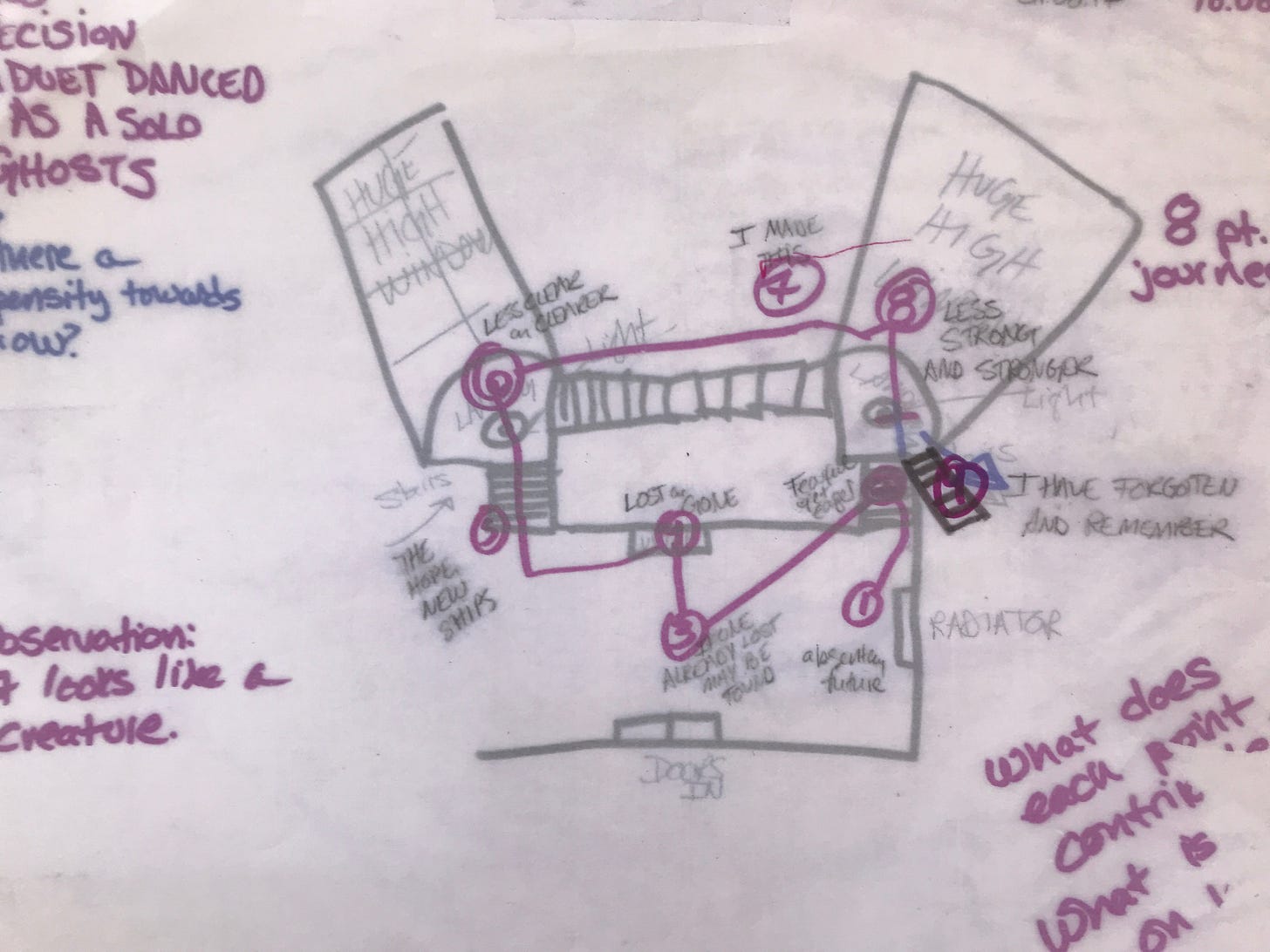

The nature of work with the spaces is improvisational, with no expectation of repetition, yet it’s often the case that motifs return as the space is visited again and again. Each period of work in the space, which may be undertaken alone, or witnessed by other members of the group, or users of the building, is followed by a period of writing and drawing, which invites the performer to create a record, intelligible perhaps only to her, of the space as she experienced it, both at the level of concrete architectural elements and a subjective level, encompassing any memories or associations that the process evoked. The unconventional blueprint(s) that emerge from this process of flowing between periods of moving in the space and drawing/writing in the studio form the basis of the repeatable score that the performer will ultimately build from this material.

Creation of the score takes place in a studio and begins with the invitation to recollect the space and to move through it, as if it is present. Gradually, through repetitions of this task, a repeatable score starts to emerge. Once its outline is relatively stable, work with the core team helps the performer to clarify the concrete parameters of the absent space where they are necessary, usually at the point at which the work would contradict or erase itself unproductively, for example, by undermining too soon a spatial relationship that has been carefully articulated. Elements of this work are rigorous and painstaking, but the process is not solely one of recreation. Simultaneously, the process invites a re-living of a performer's subjective encounter with the space.

This dance between objective form and subjective content builds a concrete yet elusive world for the spectator, drawing attention to how the body experiences and remembers absent buildings and how we might continue to dwell in them, even as they slip through our fingers. At the same time, the space in which this embodied memory unfolds is also present, sometimes coming into sharp focus, at other times receding and functioning as a prism, through which the memory of the absence space is refracted. We’re here and now, yes, but also somewhere and somewhen else. At once. As OIlalquiaga, following Benjamin, writes, “the dialectical image ‘crystallises’ past and present into one image […] that both contains and surpasses them” (2017: n.pag.). In Movement/Architecture, the image is of course unfixed, flawed and moving, a constant renegotiation, in which the building is visible by its absence, the dance that emerges a duet danced as a solo, walls and bannisters visible in a performer’s lability, which teeters on the edge of disaster, with only (only?) the embodied memory of its stability to support her.

Our initial period of R&D in HTHAC culminated with a work-in-progress showing at ImpFest 2016. On two evenings in November, we led spectators through a promenade witnessing of each performer’s encounter with her space, working our way from my functional back staircase, through Cubells’ Council Chamber and Almeida’s stairs and upper landing (viewed from the floor below). The evening ended with a collective improvisation in the large, panelled Committee Room at the front of the building, in which each of us danced through the embodied memory of our absent, individual spaces. At that stage, the work possessed a sketch-like quality, which has since been refined, as we work towards the performance that will be made from this material and performed outside the building, with the aim of sharing it, and its delicious, slightly decadent, complicated and messy possibility to spectators who may, when it reopens, visit the hotel, but will never be able to dwell in Hornsey Town Hall.

In this context, the performance events - both the ImpFest 2016 performance and the work to come - stand as an elegy to this building, at a particular moment in its history. I use elegy here not to evoke only sorrow, but in the way Samuel Taylor Coleridge means: “[Elegy] may treat of any subject, but it must treat of no subject for itself; but always and exclusively with reference to the poet. […] Elegy presents everything as lost and gone or absent and future” (2015). Coleridge’s words invite a poetics of the body, which, by moving through embodied memory retains the subjective connection to the doer, even as it is propelled through the passage of time away from the initiatial encounter. Here again, the language of architecture orientates us in our pursuit of this work as “an entity which does, rather than is” and “a machine that actualises and reproduces the realities it imagines” (Jacob 2012: 38), or in our case, lived and hope to live again.

Works Cited

Bachelard, G. (2012) The Poetics of Space, New York: Penguin. First published in 1958.

Bergman, D. (2018) “The ‘Available’ Joe Brainard” in I. Hotz-Davies, G. Vogt & F. Bergmann (eds.), The Dark Side of Camp Aesthetics: Queer Economies of Dirt, Dust and Patina, Abingdon: Routledge. Retrieved from https://www.bl.uk/. Accessed 12 July 2018

Bogart, A. and T. Landau (2005/2014) The Viewpoints Book: A Practical Guide to Viewpoints and Composition, London: Nick Hern Books.

Coleridge, S. T. (2005) Specimens in the Table Talk of S. T. Coleridge. Project Gutenberg. Available at: http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/8489/pg8489-images.html. First published 1835. Accessed 7 July 2018.

Competition for Town Hall - Hornsey: Assessor’s Notes (1935). Haringey Archive.

Hornsey to Get a New Town Hall. (1935) Haringey Archive.

Jacob, S. (2012) Make it Real: Architecture as Enactment, Moscow: Strelka Press.

Lee, C. (2017) “Introduction: Locating Spectres” in C. Lee (ed.), Spectral Spaces and Hauntings, Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 1-18. Retrieved from https://www.bl.uk/. Accessed 12 July 2018.

McCarter, R. (2016) The Space Within: Interior Experience as the Origin of Architecture. London: Reaktion Books.

McFadden, B. (2016) interview with Mary Ann Hushlak, Beautiful Confusion Collective.

OIlalquiaga, C. (2017) “El Helicoide: Modern Ruins and the Urban Imagery” in L. Muntean, L. Plate & A. Smelik (eds.), Materialising Memory in Art and Popular Culture, Abingdon: Routledge. Retrieved from https://www.bl.uk/. Accessed 12 July 2018.

Pallasmaa, J. (2011) The Embodied Image: Imagination and Imagery in Architecture. Chicestester: John Wiley & Sons.

Pallasmaa, J. (2012) The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. First published in 1996.

Robbins, J. (2016) Hornsey Town Hall to become hotel in spite of thousands calling for another way. The Ham & High, [online]. Available at: http://www.hamhigh.co.uk/news/politics/hornsey-town-hall-to-become-hotel-in-spite-of-thousands-calling-for-another-way-1-4747222. Accessed 7 July 2018.